Reinforcement Learning Primer

Reinforcement learning (RL) is an area of machine learning. The most widely used and understood area of machine learning is supervised learning, so I think it’s easy to understand what reinforcement learning is by comparing it against supervised learning. In supervised learning, you know inputs and labels (the truth values), and your goal is to come up with a model that can predict the labels only with your inputs. For example, given some facts about a home, you would like to guess what its market price is.

In reinforcement learning, you do not have this truth value, but only the feedback on how good your model is. For example, in the home price example, if there was some real estate agent that told me how good my prediction was, but never told me the answer, (despite how annoying that would be) me trying to learn what the right price will be “reinforcement learning”.

When would this kind of problem-framing be useful? Virtually all the problems that have different ways to achieve some same outcome. For example, when you play a board game like Catan and you win, you don’t win with the same sequence of actions all the time. Your board setup is different every time, you take different actions every time, but you have a consistent scoring mechanism that advises you on which actions to take.

There are a few ways that reinforcement learning is different from supervised learning:

- your inputs are not independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.). In the Catan example, your game state changes depend on your action, (which affects your opponents’ actions, etc)!

- ground truth is not known. Going back to the Catan example, you have different ways to win even given the same initial board setup, and it would be very expensive to come up with all different possible ways to win and all possible actions your opponents can take!

In the industry and academia, reinforcement learning has been used in various problems including robots doing physical tasks (moving an item from one place to another, etc), games like Atari and Go, and autonomous driving.

So now let’s try to come up with some structured problem description of reinforcement learning.

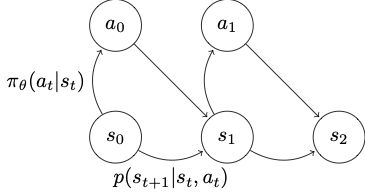

A markov decision process (MDP) is a great way to formalize the problem. A Markov decision process involves the three variables:

\[S: \text{ state} \\ A: action \\ T: \text{ transition}\]

Transition \(T\) gives you the probability distribution of the next state given the current state and action, shown in the diagram as \(p\). To go back to the Catan board game example, a state will be your current game state, which including how the board is layed out, where your settlements are, whose turn it is, etc., and your action can be any one of throwing a dice, trading resources. Your transition would indicate with the probability of 1 to your opponent getting one more lumber if your action was to trade your lumber with him, while 0 for any other states. On the other hand, when you roll a dice, there are many potential next states with different probabilities, since your dice roll is non-deterministic.

In reinforcement learning, our goal is to learn a policy that guides you to take a certain action in a given state so as to maximize the rewards. A policy is typically represented with \(\pi\). Your reward will be determined by a function \(r\) that should give you a numerical score given the current state and your action.

\[S: \text{ state} \\ A: action \\ T: \text{ transition} \\ r: \text{ reward function} \\ \pi: \text{ policy}\]Optimization

So far I’ve talked about how reinforcement learning is different from supervised learning. There are similarities as well. The key similarity is that we iteratively update the policy/model based on some objective function in both of these learning environments. In each iteration of your learning process, you will be updating the parameters of your model a bit by bit in a direction that will minimize your loss (a.k.a. optimization). In the home price example given for the supervised learning, we will want the absolute difference between the predicted price and the true price to be as close to zero as possible. In the Catan example, we could maximize the expected game score from some sequence of actions. If you want a refresher on optimizers, I think this is pretty good.

Imitation Learning

So how might we learn a policy? I mentioned earlier that reinforcement learning is different from supervised learning in that your inputs are not i.i.d., and your ground truth is not known, i.e., there isn’t necessarily the one and only correct policy. But what if there’s a good example to emulate, so there’s some sort of well agreed-upon ground “truth”? For example, if we wanted a self-driving car, can we just feed a bunch of humans’ actual driving routes (if an self-driving car would drive like I do, it might be good enough for me… I’m still alive!) and have the car learn to replicate? Well, that sounds a lot like supervised learning, and it is! We call this imitation learning/behavior cloning. So let’s talk about it before we discuss other fancy RL algorithms.

The steps to be taken are:

-

collection demonstrations from an expert, e.g., me driving in the above example. This will consist of multiple independent sequences of action, or trajectories \(\tau\).

-

treat demonstrations as i.i.d. state-action pairs \((s_0, a_0), (s_1, a_1), ...\).

-

train a policy \(\pi_\theta\) that minimizes a loss function \(L(\pi_\theta(s), a)\).

What might go wrong with this approach?

The biggest problem is the distributional shift between the expert demonstrations and our learned policy. Suppose I demonstrated a right turn, but the policy, for various reasons to be explained later, wanted to go straight; the car now ends up in a state that it’s never seen before during the training phase, because I never demonstrated what I would do in that strange part of the road! The policy, which was never trained with a particular state, takes an action that is suboptimal, and it continues to move further and further from the training trajectories.

A solution to this is to collect more data from those missing states. In the self-driving car example, a human may annotate what action to take in the new state that the policy ends up in, augment the training data, and train the policy again. We call this practice DAgger (Dataset Aggregation).

There are still other problems, such as humans not being consistent in their demonstration (Non-Markovian behavior) and multimodal behavior (multiple acceptable trajectories demonstrated given the same state). You can try mitigating these problems using a Gaussian mixture model, introducing latent variables, etc.

But even with such mitigation, imitation learning tends to underperform other RL algorithms (we’ll discuss soon!). Rewards-based RL algorithms tend to work better than imitation learning, but imitation learning is useful when the right reward function is ambiguous, rewards are not frequent, or when you want a reasonable baseline policy to start training with as you use some other RL algorithm. A more in-depth discussion of rewards-based RL algorithms will start from the next post.